Reverse engineering Lunia, my childhood MMORPG

>

September

18th,

2020

Lunia was an MMORPG by South Korean producer allm, originally launched in early 2006 and published in Brazil by Level Up! Games in late 2008. Its main premise was being an MMORPG with heavy elements of an arcade beat ‘em up, being one of the first to combine both genres.

I started playing Lunia sometime in 2009, and it was what taught me fast typing, introduced me to online forums and communities, and gracefully presented me the world of MMOs in general. The game was the biggest time-sink of young me until late 2012, when the Brazilian servers shut down. Sadly, the global servers followed suit just a year after. It’s fair to say it was far from being the largest MMO at the time, but to 9-year-old me, it was golden.

Recently, I stumbled upon some screenshots buried deep in my file archives. After a couple days of reminiscing old times in some unofficial servers that are still around - and realizing the game aged surprisingly well (although it might be just my nostalgia talking) - I decided to use the skills that I acquired since then to snoop around the game files, maybe learning some cool stuff along the way. As it turns out, that was quite successful and exceedingly fun, so here’s a quite lengthy rundown of my journey.

I probably spent over 150 hours in the last month to get up to this point, and it is still very much a work in progress. Many of the game files are still hidden or unexplored, and there’s a bunch that I still plan to do with the extracted assets. With that, I may update this post (or write follow-ups) in the near future if I do so.

0. Disclaimers

First of all, I am aware that the legality of this is a gray area. Although I’m pretty sure at this point Lunia could be categorized as abandonware, I still don’t think sharing the game files are, legally speaking, a very good idea, so I won’t be releasing the decoded stuff here other than small snippets or screenshots. Still, if you want to try it yourself, all of the base files are somewhat easy to find if you know where to look for.

Secondly, most of this exploration was far out of my comfort zone. Other than a bunch of practice with Python scripts, I had barely any experience with most of the tech and strategies used here. Despite Computer Graphics being a field that I have always been very interested in, I had never touched 3D modeling, 3D animation, shaders and the like before this. Furthermore, my experience with reverse engineering in general is very, very brief, and game development was also never my thing, although I tried my hand at it a couple of times in the last years. Because of that, do take all of this with a big grain of salt: I’m sure there are many inaccuracies and false assumptions below. This was a great learning project starting from very little previous experience, so please do get in touch if you find anything out of place.

Based on both points above, this is not supposed to be a guide. This is more of a writeup from my exploration and storytelling of my discoveries. Although it’s not a tutorial, it probably serves as one if you ignore all my rambling. Also, I had no set goal at any stage whatsoever: I just kept taking whatever path I felt like and doing whatever I was up to at the time, so that’s why my steps may feel unordered and out of place.

Additionally, this is not an incentive or recommendation for you to play on an unofficial server. I won’t be giving any pointers on how to access them, but, again, the information is easily available online if you search for it. However, as Lunia is still “active”, from now on I will be talking about it in the present tense. Do be aware that, officially, the game servers - and, being an MMO, the game itself - are unavailable.

Finally, all of this was done solely for educational purposes. There is absolutely no intention of breaking copyright or redistributing any proprietary files, nor disrupting any active services. This is a writeup of a technical exploration fueled by curiosity, passion and nostalgia.

1. What is Lunia?

Lunia, originally called “Lunia: Record of Lunia War”, and in a later update renamed to “Lunia Z”, is an MMORPG with a big focus on PvE content, individual instanced stages and a rather linear progression - far from the open-world, quest-driven MMOs that dominate the market today. It consists of around 150 maps, or “stages”, of increasing difficulty, leveling your character from level 1 to 99. You can also be “reborn” once a month, as many times as you like: doing so resets your character back to level 1, giving you some cool stats bonuses and cosmetic wings in return, stacking up every time you rebirth. Most of the stages can be played with a party of up to 5 people, with a maximum party size of 12 for special maps or events. Lunia also has microtransactions, which definitely gives the game some “pay-to-win” vibes.

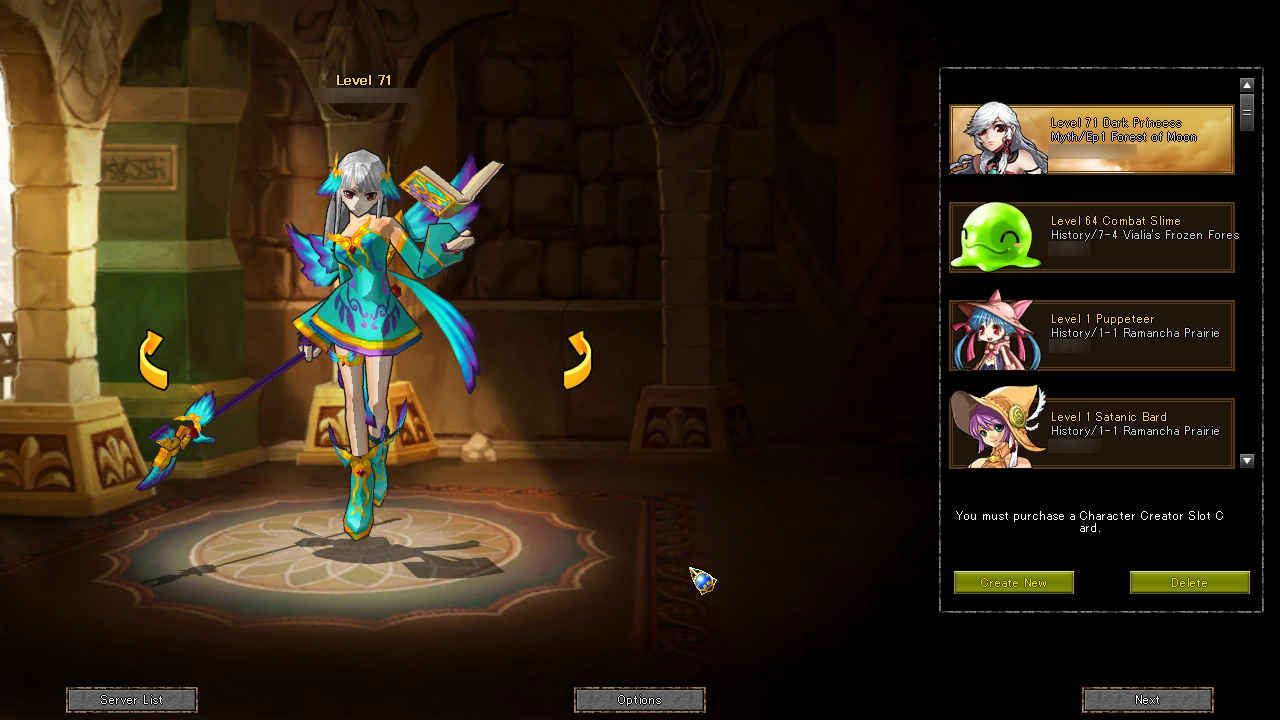

Instead of creating and customizing your character like you would in most MMOs nowadays, you choose from 17 characters (originally just 3, with 14 more added to the roster via updates through the years), each having a well-defined place in Rodesia, the continent where Lunia takes place. Here’s the character creation screen:

Just so you can follow along when I use any game-specific terms, here’s a brief description of the main stages and collections of them:

- Town Square: Main game hub, where most shops are located and players idle while fishing or selling stuff (more on this below).

- History (Level 1-70): The game launched with only 3 episodes of 10 stages each, consisting of the main storyline. Later, it was gradually expanded to 7 episodes.

- Legend (Level 30-70): Legend has the same first 6 episodes from History, with increased difficulty.

- Bonus (Level 65+): Consists of 3 episodes with 7, 7, and 3 stages each, respectively. Longer levels with a big difficulty spike, hard to clear them by yourself. Gives some quite cool items and item sets. Each episode has a different theme and storyline.

- Myth (Level 70+): Unlocks only after a rebirth. Has 6 stages and a somewhat long questline to unlock each of them. Gives exclusive item sets that can only be used in Myth/Devildom stages. Group content, not intended to be solo’d.

- Devildom (Level 80+): Introduced very late into the game’s life, also requires a rebirth, and… I don’t know or remember that much, actually. Never reached that when I was little, and didn’t bother to play that much in unofficial servers.

Some other relevant (and fun!) game mechanics were:

- Trading, Personal Shops, and Open Market: Trade items and currency with other players directly, set up your shop at the Square while idle, or put your items up for sale in the Open Market for anyone to purchase at any time.

- Player vs. Player: A dozen or so PvP arenas for up to 8-vs-8 combat.

- Guilds: Communities of up to 200 players, with extra perks when playing together.

- Families: Essentially smaller guilds of up to 5 people, originally made to pair new players with experienced ones.

- Item “fortification” and “light fortification”: Improve your items by spending reagents, heavily based on RNG. The latter would also make your equipment shinier.

- Fishing: Leave your character fishing while idle to turn bait into various types of fishes, which can be sold for gold or traded with NPCs for many valuable items and resources.

- Pets: Choose between dogs, cats, fairies, dragons, unicorns, and a dozen other small creatures that follow you around and give you stat bonuses - but only if you feed them.

- Slime Racing: Bet coins on a fully RNG-based NPC race. Basically a Roulette numbered from 1 to 9.

- Achievements: Complete various milestones and rack up achievement points, which in turn gives you some colored stars after your name for clout.

While looking for some information about Lunia (which the internet has surprisingly little of), I found two series of articles by IGN from 2007, sometime around the North America open beta launch, talking about the game’s initial premise and development, and they’re quite detailed. Here’s Record of Lunia War Interview Part 1 and Part 2, as well as Record of Lunia War Diary #1, #2, #3 and #4, both of which were a great read before cracking the game open.

2. Scratching the Surface

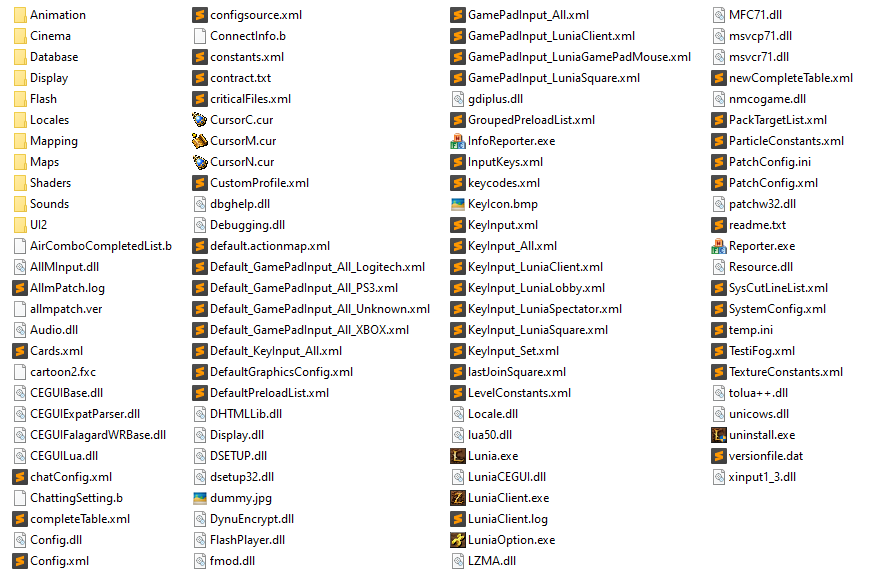

Initially, what I had to play around with were the game client files. I managed to get my hands in two clients from different unofficial servers, as well as the original one from the old days of the Brazilian server. I later found out that there were no big differences between the three of them other than the localization, so from now on, I’ll be referring to all of them as a single client. Here’s the game root directory, with a total size of around 1.5GB:

Together with the obvious game executables and cursor icons, most of the files at the root were configuration files. Key bindings, player preferences and graphics options, all stored in .xml text files with a bunch of comments in Korean. A few .dlls that grabbed my attention were FlashPlayer.dll, lua50.dll and tolua++.dll, LZMA.dll, and half a dozen with “CEGUI” in the filename.

The Cinema/ and Flash/ directories contained hundreds of .swf files that can be viewed with something like SWF File Player. Those are all Flash animations that are extensively used throughout the game. Alongside some of them, there were also a few sprites in the .dds format. Sounds/ had a hundred .ogg and .wav sound files, which were the game’s main theme songs, a bunch of background music and general ambience SFX. It also contained files Sounds.cfp and Sounds.cpv, extensions that I had never seen before.

All the other folders (Animation/, Database/, Display/, Locales/, Mapping/, Maps/, Shaders/ and UI2/) had only two files in each of them: a .cfp and .cpv, named the same as each of their respective parent directories, exactly like the ones at Sounds/.

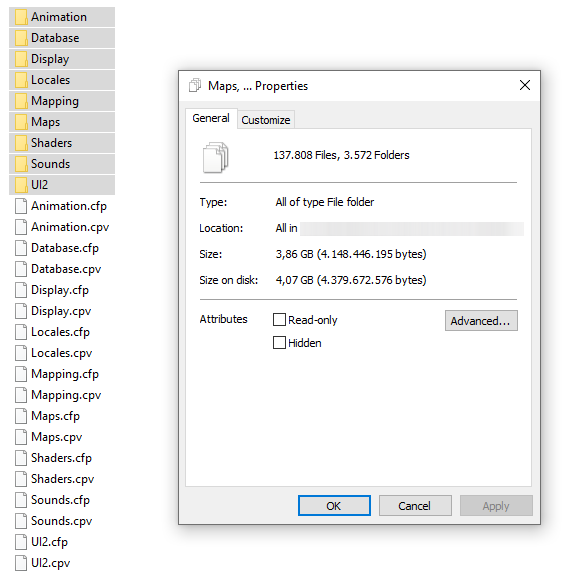

When trying to figure out what those two file types were, no obvious result showed up. Only when searching for the extensions together with “Lunia”, I managed to find some forums posts that guided me to QuickBMS, which has a handy unpack script for .cfp files, seemingly Lunia-exclusive. Upon inspecting the script, the file type is a simple binary file with a bunch of string filenames and its LZMA-compressed binary data (hence the LZMA.dll found earlier!) concatenated. As for their .cpv counterpart, they went completely unused by the script without any data missing as a result. By looking at its binary data, my best guess is that they simply serve as index tables for the game to be able to directly locate any specific file inside the archive. When extracted, the 1.2GB collection of 9 pairs of .cfp and .cpv files turned into over 130.000 files, totaling around 4GB:

There we go! Here are the interesting pieces that were unlocked by simply extracting the archives:

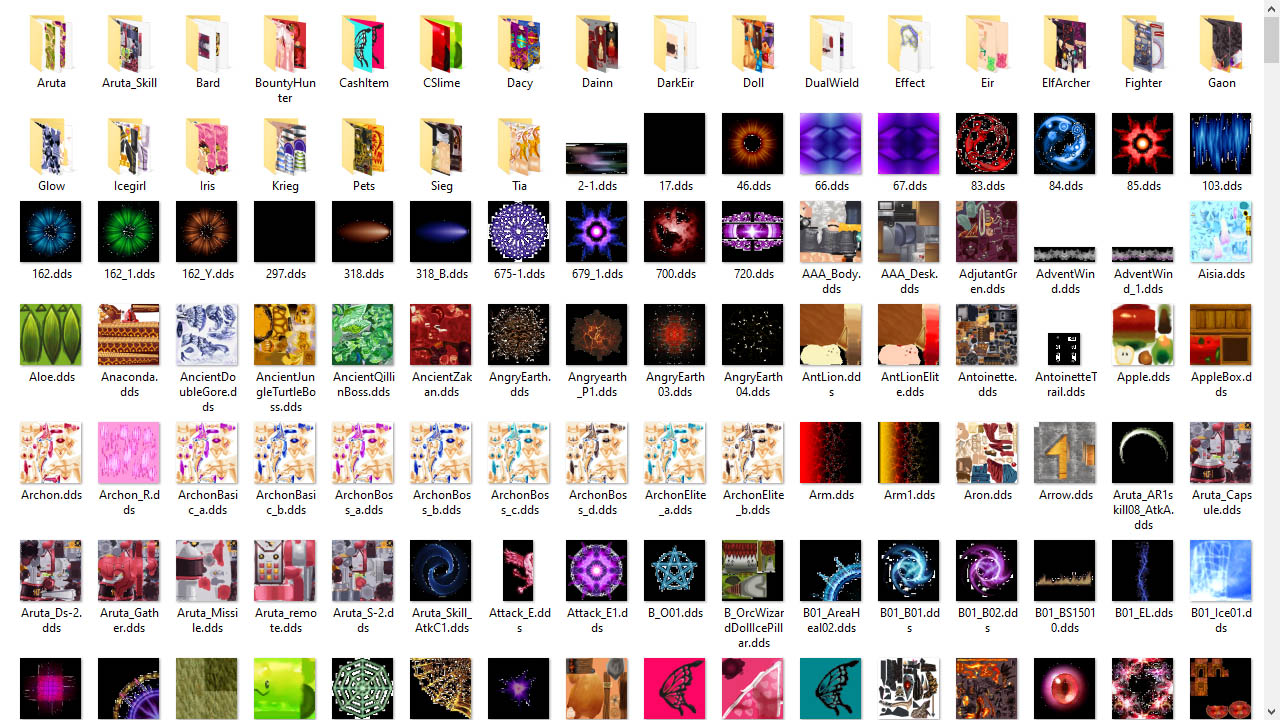

- Over 25.000 item and skill icons at

Display/Textures/, all in.ddsformat (screenshot below). - All game strings at

Locales/, in more weirdly ancient.xmltext files. Quest texts, NPC phrases, item and skill names/descriptions, achievements and everything else. - Over 15.000

.ddstextures for every single 3D model in the game atMapping/, from characters to pieces of equipment to skill effects (screenshot below). There were also around a hundred textures for the stages’ visual elements (trees, rocks, buildings…) atMaps/*/Shared/. - Hit sounds, character attacks’ SFX, voice lines and a bunch of other sound snippets at

Sounds/all in the same.oggand.wavformats, along with copies of the same ambiance sounds and background music that was outside the.cfparchive, for some reason. - All UI visual elements as

.tgafiles and more.swfanimations atUI2/, mainly insideUI2/imagesets/andUI2/Stage/. - A lot of simple text files with different extensions everywhere. Some of them describing UI element positioning (

.layout,.looknfeel), and mainly a load of.xmldetailing camera configurations, coordinates for asset placement in stages, and just generally referencing assets via their file paths.

![]()

For the image assets, XnConvert made it easy to batch convert both .dds and .tga file types to the more common .png extension.

However, a lot of points still left me puzzled:

- Most of the files at

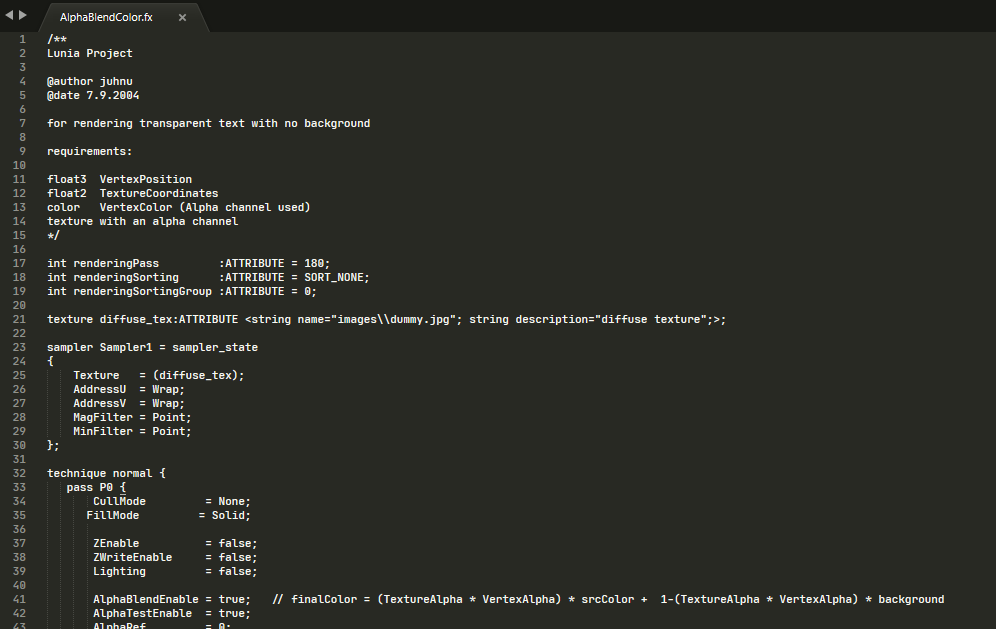

Shaders/were.fxcones. Upon further research, those appeared to be compiled HLSL shaders. As Lunia’s minimum requirements ask for DirectX 9.0, that made sense. However, as those are compiled files, trying to decompile those seemed way out of my league - or interest - at this moment. - Lots of stuff in

Animation/were.SkinnedMesh,.Skeletonand.SkinnedAnimfiles, with more atMaps/*/Objects, all seemingly custom formats, specific for Lunia. No obvious way of opening them, but I suspected those contained the 3D models, armatures/rigging and animation sequences, respectively. - The

.LuniaMapfiles inMaps/probably described the stage, I supposed. Also seems to be completely custom. - Where are the fonts?

UI2/fonts/had a ton of.xmldefining different font styles by having different variables in them, but no.ttffiles like I was expecting. However,Shaders/had a couple.fxcwith a pairing.fxof the same name. When opening one of them (screenshot below), it surely had something to do with rendering text. Could the fonts be fully rendered via shaders? Is that even possible? - What about all the equipment stats, drop tables, and all the numbers that a hardcore player would love to have at hand? I supposed that for bigger flexibility for balancing tweaks and the like, those would not be in the client files, but server-side.

It’s also interesting to note the information in the file header: the game is referenced as Lunia Project; the file author, juhnu, is possibly Juhani Honkala, who is credited as “Lead Graphics Programmer / Technical Director”; and the file date, 2004 - Lunia was launched in 2006.

At this point, after some days of exploring all files and reading most of them from top to bottom while trying to understand how the big web of .xml files relate to each other, I got pretty tired of that. Being happy as a result of extracting all item and skill icons as well as all UI elements, I felt like playing with them for a bit…

3. Playing with UI

It had been a few years since I had last made a project with a graphical interface. With the spark of motivation from having those thousands of 32x32 icons in hand, I felt like coding a clone of Lunia’s inventory window. Here it is, in-game:

Although I’m almost completely sure Python is not the greatest tool for that, it is the one I am most comfortable with, so I chose Pygame as the graphical library. I had tried to use it a couple times in the past, but never managed to build anything that looked polished enough, probably for the lack of general programming experience at the time.

One common misconception is that Pygame is a game engine. It’s actually way lower level than that: Pygame is a set of Python modules built on top of SDL, but, for my specific use case, it served mostly as a simple library that allowed me to draw images at certain positions a bunch of times a second. And having to write code to make higher-level functions out of that is exactly my cup of tea.

I first started taking screenshots of Lunia’s inventory and modifying pixels here and there, like expanding the item slots to a single 8x8 grid instead of 7 separate 5x4 bags, simplifying the equipment tabs to only one and removing the currency altogether. After a while of getting a feel for Pygame, I managed to make the item icons draggable, have them snap to the actual slots, draw that cute hover effect and have a solid back-end for all of that: well-thought-out data structures to store inventory and item properties. It was at this point I realized I needed a big refresher on some Object-Oriented Programming concepts, which led me to one of Raymond Hettinger’s talks - Hettinger has done excellent work as a Python Core Developer, and if you consider yourself an intermediate Python developer, I highly recommend watching all of his talks, which was exactly what I did in the days that followed: binge-watched them as if they were a Netflix show.

The next challenge was to show the item quantities, in the lower right corner of their icons. Of course, a requirement for that would be the fonts, which I still hadn’t managed to find in the game files. With that, I decided to just screenshot the numerical characters and manually create a spritesheet with Photoshop and some patience. Next, some more hours of work went by to build higher-level functions that drew strings of numbers at the appropriate positions.

Then, I spent some more days refining the code (and rewriting it all from scratch to apply my newly gained Pygame and OOP knowledge) and implementing some of the remaining, most obvious features: item swapping, equipping and unequipping, stacking and splitting, and a bunch of other small touch-ups. It’s at those times you stop to appreciate the fine art of UI/UX development: it turns out game UIs have so many small details that we take for granted when playing but stick out like a sore thumb when you forget to implement them.

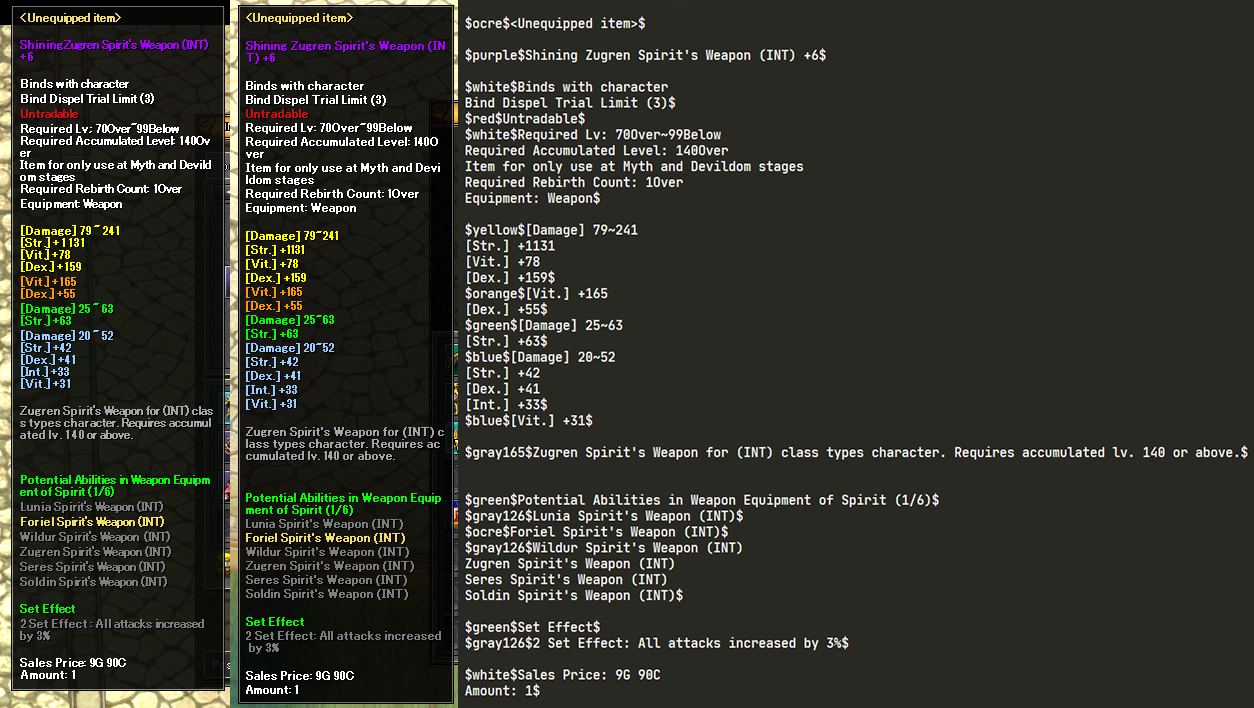

For my next trick, I figured I would try to draw the description textboxes. You know, when you hover over the item, and a textbox pops up with its name, properties, stats, description, and all the cool stuff? Here’s another screenshot showing the original thing:

Great! Now I just grab the font files and… well, there are none. I will have to make them by hand, again. After a bit of in-game exploration, it turns out all of the fonts used throughout Lunia can be summed up in four styles, three of them present in the screenshot above: regular (e.g. currency amount, at the bottom), bold (e.g. item description textbox, window title), regular with stroke (e.g. equipment tabs, at the top), and bold with stroke. As shown, they can be in varying colors (and stroke colors), and sometimes even sizes - I chose to ignore different text sizes for now. Upon further inspection, all of the styles derived from the basic, regular one: the stroke is done by simply painting the 4-connected pixels, and the bold sprite is simply two of the regular one, the second being drawn offset one pixel to the right.

Well, I once again built the characters’ spritesheets by hand. Thankfully, as with most of the game’s assets, they are quite fixed in size and there’s no anti-aliasing at all, giving them that pixel-art feel which I adore. Having the four spritesheets ready (which could be just the regular one, but I figured it was easier to “harddraw” all of them instead of using code to apply the bold and stroke effects), some more days went by on writing a very flexible and optimized text drawing module, complete with text coloring, left/center/right alignment, line breaks and text wrapping. The character widths are variable, but the heights are, for the most part, constant. However, the horizontal spacing is quite wonky. For my implementation, I decided to ditch any attempt at kerning and just set a constant 1-pixel spacing for every character, which, if I do say so myself, turned out better than the game itself. To test it isolated from the rest, I decided to write a basic text editor:

With that out of the way, I rewrote the code for the item quantities to now use the shiny text module. As a bonus, I also used it to draw the window title, now being able to freely rewrite it instead of being baked into the background. Cool! Now I just have to draw the description textbox itself, and… then I realized that’s not going to fit into my measly inventory window.

Okay, I could simply make the application window larger, but where’s the fun in that? What if I made the window draggable? Of course, that meant having to basically rewrite the whole thing once again as to, per best OOP practices, have a Window base class for every other window to inherit from. In turn, that would give me not only draggable windows, but multiple ones. And they may have different sizes and titles. And they may overlap. And I would have to deal with how to choose which one to send input info to. At this point, the project scope exploded, and I decided to just go for it. After a couple more days, I now had a full window manager thing going on. Once again, many small UI/UX elements and concepts that I always took for granted and had to account for.

I then rewrote most of the initial project’s code, adding another window modeled after one of the game’s fishing windows, with the (fake, fixed) total fish counts. Some more hours into a new description textbox module, and another bunch into building a parser to process formatting tags for me to easily mix and match different colors in a single block of text…

For now, the large item description and stats shown are hard-coded. I had the item names and descriptions from the localization files, but not the stats or the other properties. However, the code is flexible enough to handle that whenever I get my hands on them. Also, I later packed up all 25.000+ icons into a single spritesheet using TexturePacker, as that makes loading them into memory way quicker.

As the video compression kinda kills it, here’s an uncompressed side-by-side comparison of the textboxes, with Lunia’s on the left and mine on the right, together with the source text with my formatting tags used to generate it:

All in all, the window manager / inventory clone runs at around 500-700 FPS on my machine (Ryzen 5 3600), with lots of pending optimizations still. Of course, there’s a lot more that can be done, and I do plan on spending way more time working on it. One of the ideas that sounded interesting at that moment was to build some sort of model viewer, so I could have my 3D character dressed up with the currently equipped items. However, to do that, I would need the actual 3D models, of course. So, I went back to scavenging…

4. 3D Meshes

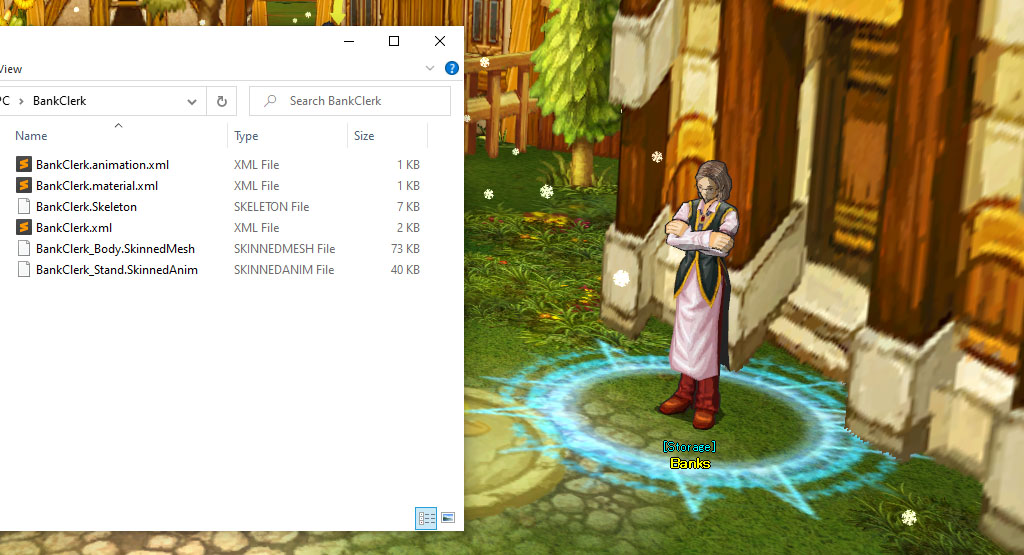

I had never fiddled with 3D stuff before, but I knew some basic concepts and I’ve been wanting to play with modeling for quite a while now. Having barely any previous experience meant that trying to reverse engineer Lunia’s 3D files was a quite daunting task. Well, I already had all the models’ textures, but not the models themselves. My best guess was still the Animations/ directory: if I navigated to Animations/AlliedNPC/BankClerk/, here’s what I got, alongside the Bank NPC at the Square, which I assumed the files represented:

BankClerk.material.xml referenced the model texture located at Mapping/; BankClerk.animation.xml linked the .Skeleton and .SkinnedAnim files, and set the animation variables speed to 30 and playback to 2, whatever those meant; and BankClerk.xml simply defined an object of type Character::SkinnedModelInfo that tied everything together.

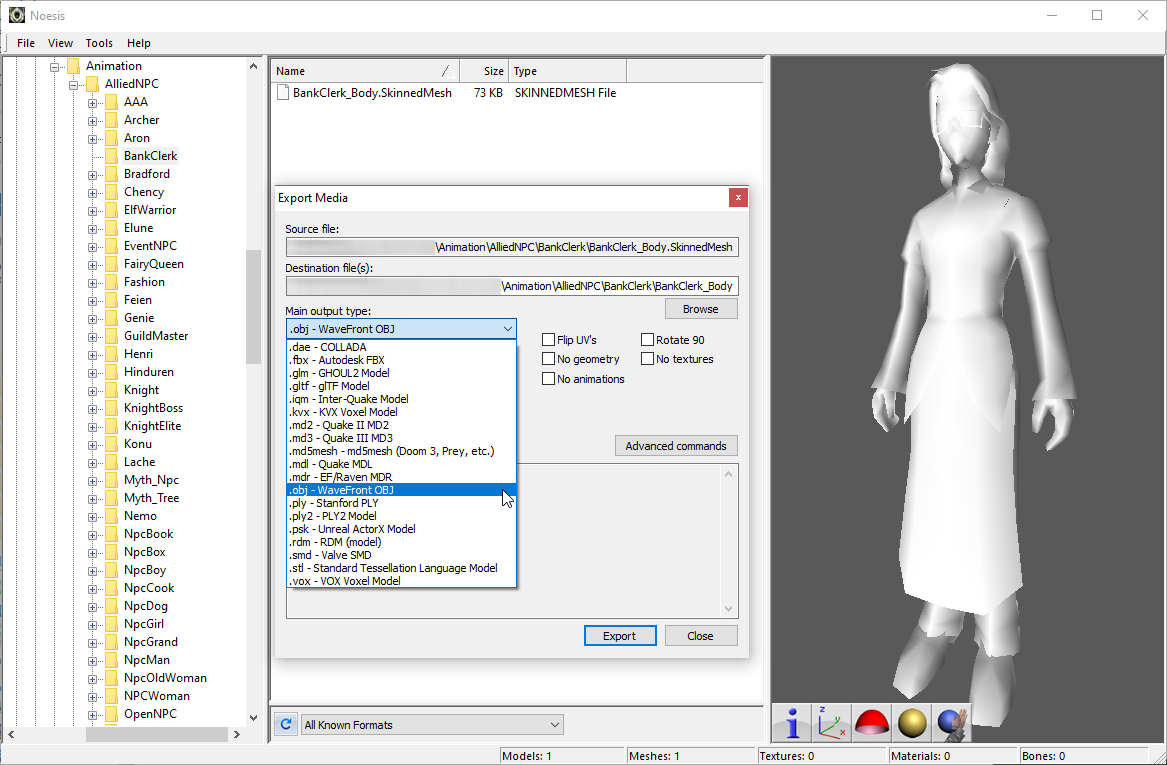

After lots of searching around the web for something that could make some sense of those files, I finally found Noesis, which seemed to be a tool for opening and converting 3D models, with an easy API for people to write plugins for custom file types. With the program itself, I also found a custom plugin for .SkinnedMesh files. Bingo!

Well, Noesis has 20 or so file extensions for me to choose from, and none of them were familiar to me. Here’s when I realized I would have to pause for a while and learn a bit about 3D animation before continuing. First, I decided to set the initial goal of being able to export the models (textured, of course) to something like Blender. I also quickly found out that the most friendly, and possibly common, filetype for 3D models is the .obj extension.

To start, I learned that a (basic) textured 3D model consists of:

- A list of vertices, or 3D points, usually represented by 3

floats. - A list of faces, usually of triangles, each defined by a subset of the vertices. Together with the vertices, they form the model’s mesh.

- A flat texture file, usually a square image.

- A UV map, which defines the relationship (mapping) between the mesh and the texture.

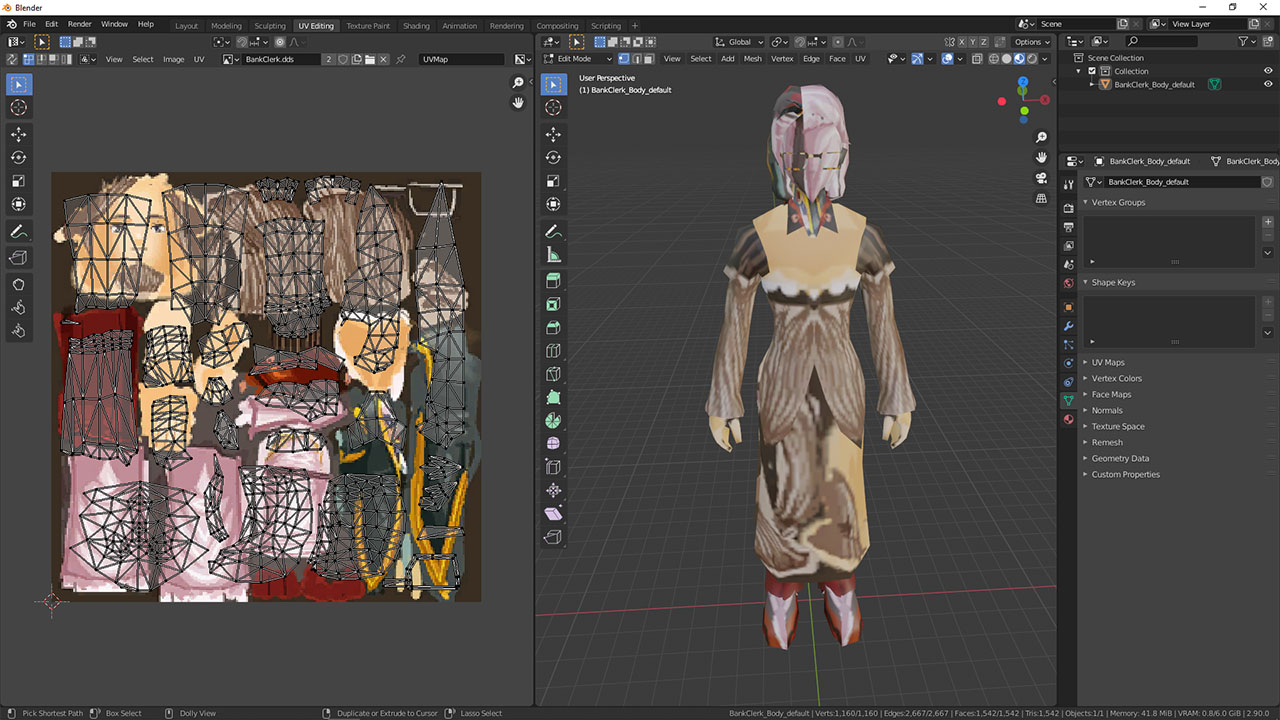

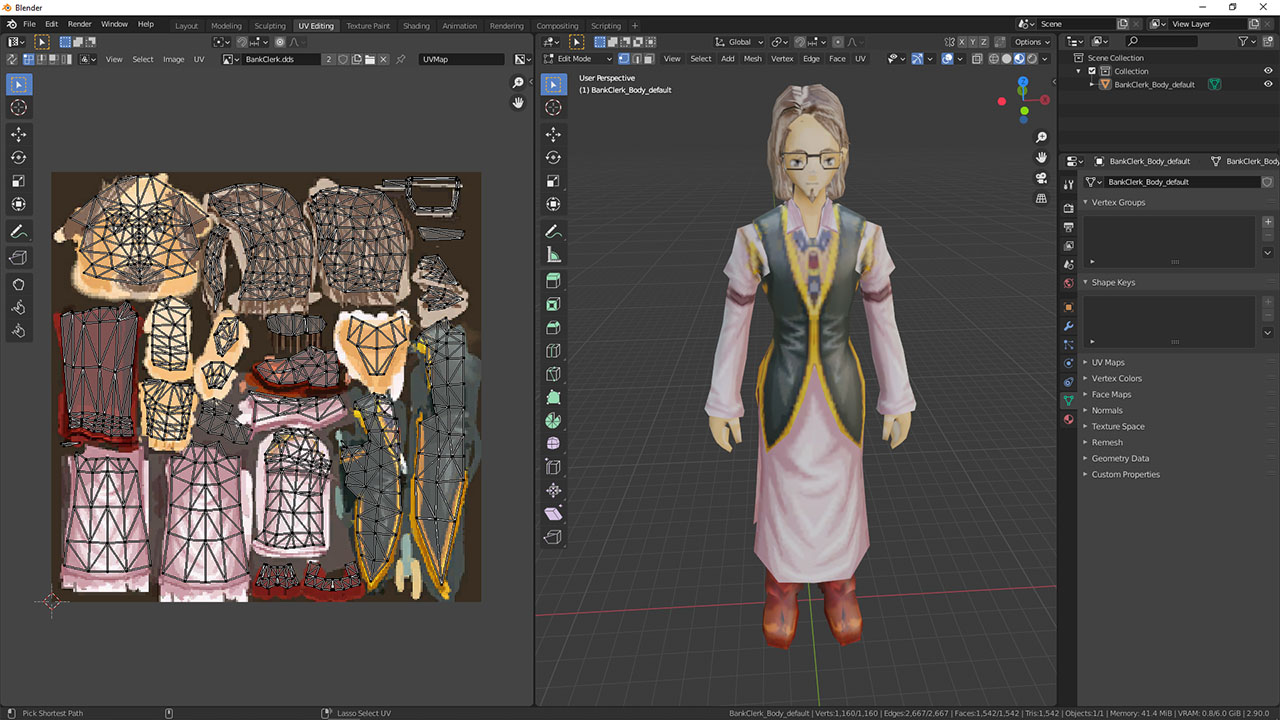

Well, I already had the texture file. Maybe the other 3 elements were in the .SkinnedMesh that Noesis loaded? Indeed they were, plus a list of vertex normals, which were all successfully exported to an .obj file. I then spent a few hours learning Blender’s interface and key bindings, imported the newly generated file, and all was good. But when trying to add in the texture, the UV map seemed a little bit out of place…

Although using sy-1 (Blender shortcut for “scale -100% in the y axis”) seemed to fix it, it also introduced a subtle vertical offset. It’s easy to notice the texture being a bit out of place on the character’s shoes:

I figured I would try to modify the conversion script so it flipped the UV map on the y axis by applying the transformation (x, y) -> (x, 1-y) on all vertices (the Flip UV's option in Noesis flips it in the x axis instead). However, to do that, I was forced to understand what the script was doing, and, consequently, what exactly that custom filetype was. After exploring the script and the file’s binary data, the (almost) full definition of the .SkinnedMesh filetype is:

// Little Endian

// 4-byte ints, 4-byte floats, 2-byte shorts, 2-byte chars (UTF-16)

int N; // length of the model name

char[N] modelName; // string for model name, ending with 0x0000 (\0)

int V; // # of mesh vertices

int I; // # of mesh vertex indexes (3 * # of faces)

int unknown[6]; // unknown

short faces[I]; // mesh faces, 3 by 3

int V; // # of mesh vertices (same as before)

float vertices[3*V]; // mesh vertices, 3 by 3

int V; // # of mesh vertices (same as before)

float vertexNormals[3*V]; // vertex normals, 3 by 3

int V; // # of mesh vertices (same as before)

float uvMap[2*V]; // UV map vertices, 2 by 2

int V; // # of mesh vertices (same as before)

// a lot more data, unknownAnd it worked, without the small inaccuracies inserted by Blender! Here’s a more pronounced example, in which the back model was the one that had the UV map flipped by Blender, and the one on the foreground had it flipped by my modified script:

Here’s the snippet of (really ugly) Python code that I wrote to flip the y coordinate of all UV map vertices:

uvMap = bytearray(uvMap)

for i in range(4, len(uvMap), 4*2):

y = struct.unpack("f", uvMap[i:i+4])[0]

uvMap[i:i+4] = struct.pack("f", 1-y)

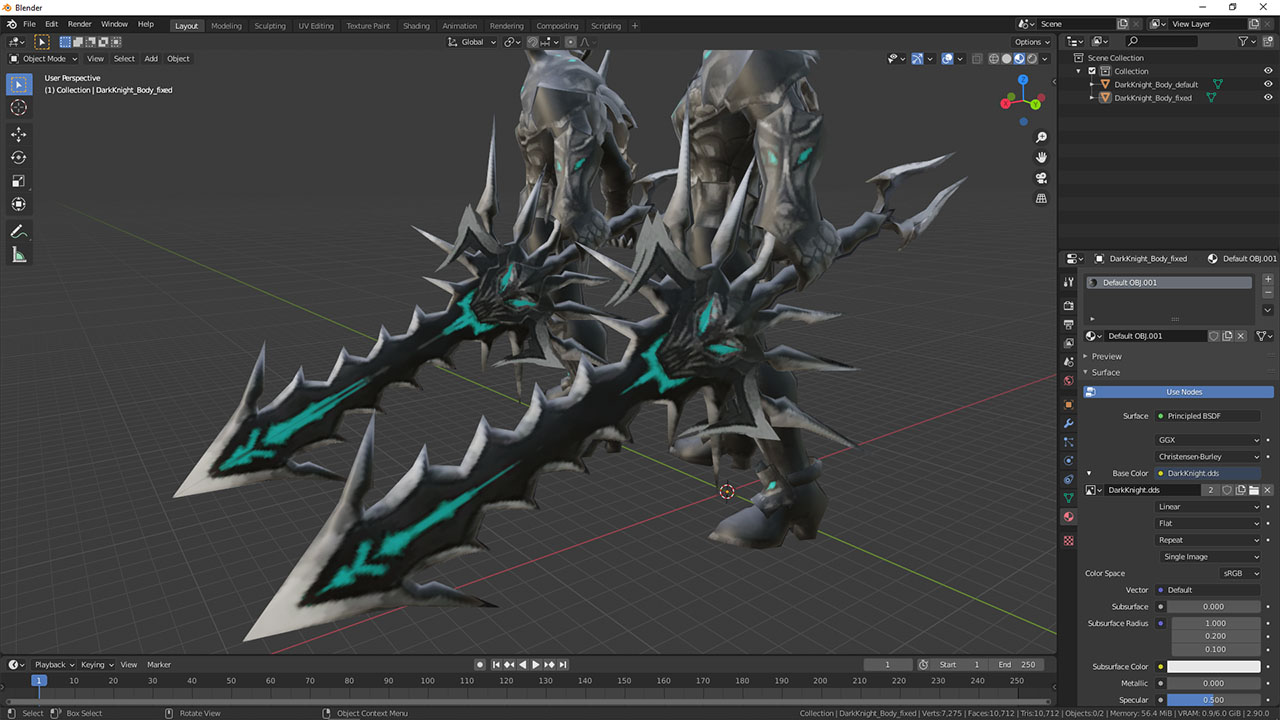

uvMap = bytes(uvMap)With that fix, around a dozen Blender tutorials, and going face first into that rabbit hole, I exported some other models and textures and rendered a basic scene:

It’s interesting to note that, for the character on the right, I had to piece together the models for each body part, as there’s an individual model for every piece of equipment in the game. I decided to pick my favorite equipment set: the one from the Forest of Water (Myth 2), which matches the one my character is wearing in some of the screenshots shown earlier in this post. It’s also clearly in a different pose than in-game, I wonder why…

5. 3D Rigging and Animations

A 3D rig, also known as an armature or skeleton, is a collection of “bones” that each relates to a subset of vertices from its mesh and may be connected between themselves. They mainly serve as a tool for creating smooth animations for the model by automatically deforming the appropriate vertices without having to manually manipulate every single one of them for every animation frame. Most rigged models are usually related to characters, but anything that moves may have a skeleton as well. In the context of Lunia, other than all playable and non-playable characters, most of the spells also have an armature attached.

With that in mind, it became pretty clear that .Skeleton probably defines the bones, and .SkinnedAnim should list a series of frames and the rig’s movement between them. Unfortunately, I couldn’t find any previous work done on any of those files anywhere on the web. Although that Noesis plugin handled the meshes, there’s absolutely nothing regarding armatures or their animations. So this time I had to go barehanded.

At this point, the BankClerk model was the one I was the most familiar with, and it looked as simple as a humanoid model could get, he only had one of each: .SkinnedMesh; .Skeleton; and .SkinnedAnim, and being a humanoid, I figured his correct skeleton and movements would be quite easy to recognize. With most of the .SkinnedMesh figured out and the assumption that .SkinnedAnim probably acts on the .Skeleton, it was easy to choose the next one to tackle.

This was my first time analyzing a binary with no information before. I thought a first good step would be to open a couple other .Skeleton files as well, so I chose Animal\Bear\Bear.Skeleton and AlliedNPC\Knight\Knight.Skeleton and kept comparing the three of them with each other to spot similarities and differences.

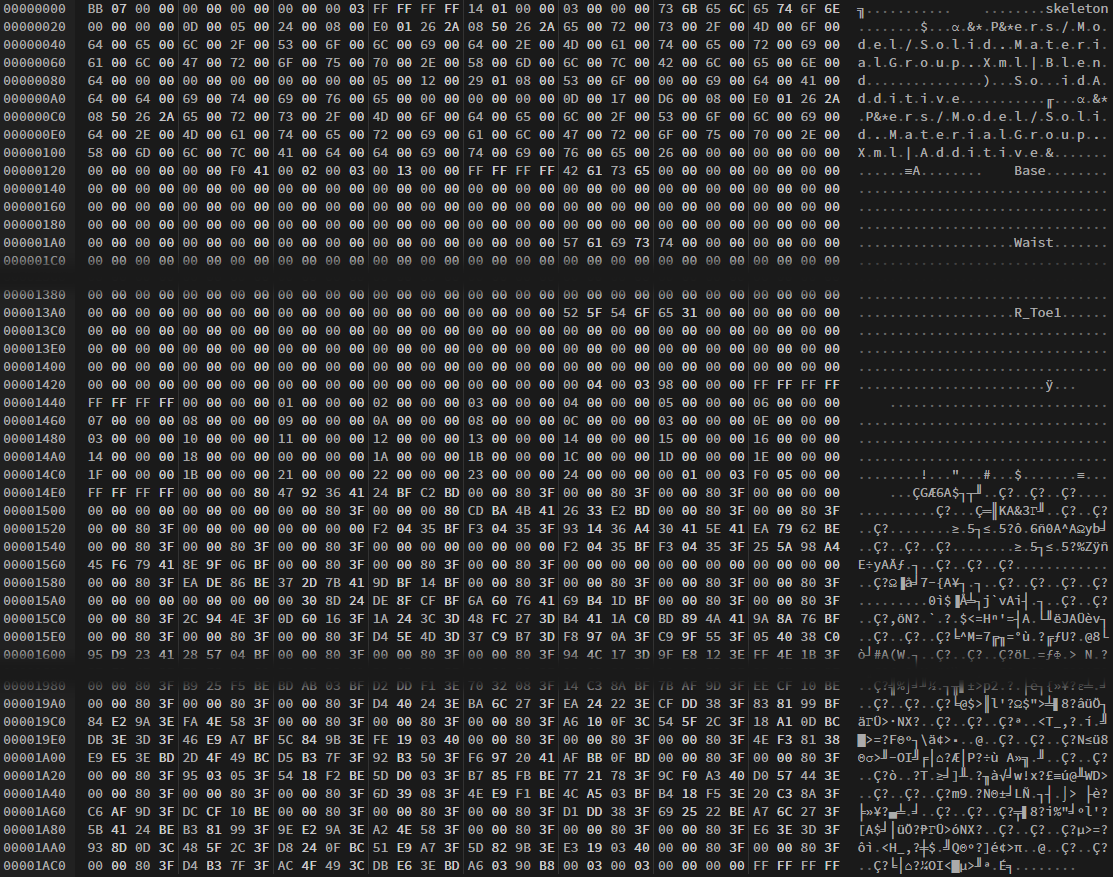

The BankClerk.Skeleton file had 6880 bytes in total. Here’s the most interesting parts of the file’s binary data, from HexEd.it:

Based on some assumptions taken from the .SkinnedMesh exploration, I started taking notes. Well, the first bytes seemed simple enough: some UTF-16 strings containing what looked like file paths…? Considering the SolidMaterialGroup.Xml string, I supposed they referenced the other related files. Next, I spotted quite a couple FF FF FF FF sequences: they seemed to be separators for different data sections: whenever the byte patterns changed, there was a FF FF FF FF between both parts.

After the UTF-16 strings section, there were 38 UTF-8 strings of 128 bytes each, zero-padded, of quite suggestive content, leading me to believe they were all bone names: Base, Waist, Chest, Chest1, L_Shoulder, L_UpperArm, all the way to R_Thigh, R_Calf, R_Foot and so on. I wonder why they are all of fixed length, as most of the 128 bytes for each string are wasted.

After that (if you are following along on the image, this is at line 00001420), comes:

00 04 00 03: I had no idea what those are, but they are in all.Skeletons.98 00 00 00: that’s152in decimal, which happens to be exactly38*4! Don’t know what to do with that, though.FF FF FF FF FF FF FF FF: two separators, yay.- 37

ints:0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 8, 12, 3, 14, 3, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 20, 24, 0, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 27, 33, 34, 35, 36. It’s a list of integers going from 0 to 36, almost sorted, with some repetitions. 00 01 00 03: Same, no idea, is in all.Skeletons.F0 05 00 00:1520in decimal…38*40! So what?FF FF FF FF: another separator.

Now came the scary part: 1528 bytes (that’s 38*40 + 8…) until the last 4, another separator. Again, if you are following on the image, that’s at line 000014E0.

I assumed there had to be at least 38 triplets of floats somewhere, to represent one vertex for each bone name found earlier, somehow. As 1528 is indeed divisible by 4, the size of a float (or int), I decided to break it down into 4-byte groups, and doing that, I noticed there were lots of triples of 00 00 80 3F. By looking at the character representations of the binary data back in the image, they can be easily spotted by the sequence ..Ç?..Ç?..Ç?. With endianness in mind, it turns out that 0x3F800000 in IEEE 754 is exactly 1.0! That left me confident I was on the right path.

Taking the 1528 bytes, ignoring the first 8 (00 00 00 80 47 92 36 41), and splitting the rest into 38 groups of 40 bytes (10 floats) each gave me a hunch to further split those 10 floats into groups of 1, 3, 3, and 3. Here’s a snippet of that, with prettier whitespace:

24 BF C2 BD

00 00 80 3F 00 00 80 3F 00 00 80 3F

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

00 00 80 3F 00 00 00 80 CD BA 4B 41

26 33 E2 BD

00 00 80 3F 00 00 80 3F 00 00 80 3F

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 F2 04 35 BF

F3 04 35 3F 93 14 36 A4 30 41 5E 41

EA 79 62 BE

00 00 80 3F 00 00 80 3F 00 00 80 3F

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 F2 04 35 BF

F3 04 35 3F 25 5A 98 A4 45 F6 79 41

[...]

A2 4E 58 3F

00 00 80 3F 00 00 80 3F 00 00 80 3F

E6 3E 3D 3F 93 8D 0D 3C 48 5F 2C 3F

D8 24 0F BC 51 E9 A7 3F 5D 82 9B 3E

E3 19 03 40

00 00 80 3F 00 00 80 3F 00 00 80 3F

D4 B3 7F 3F AC 4F 49 3C DB E6 3E BD

A6 03 90 B8 00 03 00 03 00 00 00 00Taking those floats and converting them into decimals yields:

-0.09509

1.000 1.000 1.000

0.000 0.000 0.000

1.000 -0.000 12.733

-0.11045

1.000 1.000 1.000

0.000 0.000 -0.707

0.707 -0.000 13.891

-0.22117

1.000 1.000 1.000

0.000 0.000 -0.707

0.707 -0.000 15.623

[...]

0.84495

1.000 1.000 1.000

0.739 0.009 0.673

-0.009 1.312 0.304

2.04845

1.000 1.000 1.000

0.999 0.012 -0.047

-0.000 0.000 0.000Assuming they keep their order, each of the 38 bones has a name and 10 floats related to it. If I enumerated them from 0 through 9, for each of the groups of 10:

- 0: Unsure. Definitely a

float, though. - 1, 2, 3: Unsure. In most of the

.Skeletons, all1.0s. Rarely, may have a slight (±0.2) variation. - 4, 5, 6: Unsure. In all of the

.Skeletons, are in the interval[-1.0, 1.0]. - 7, 8, 9: Those were all over the place. Looked like coordinates.

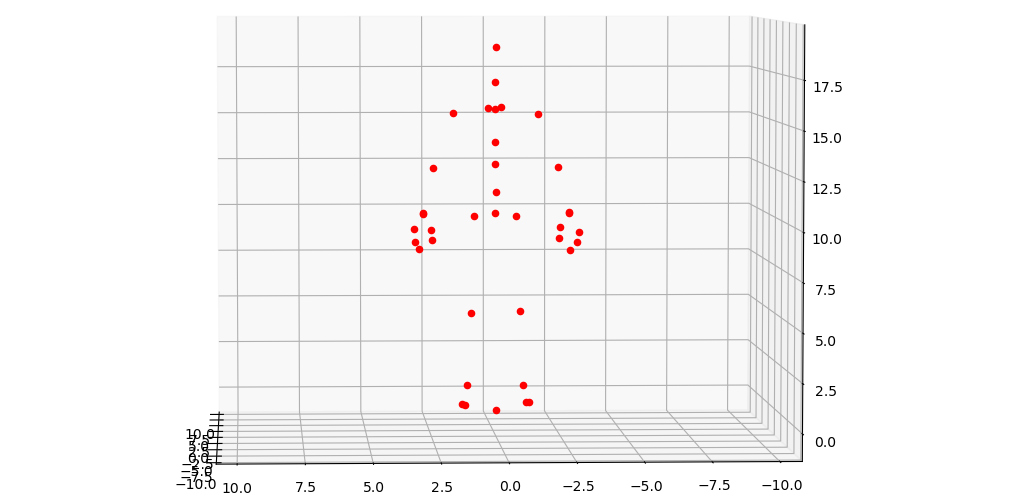

Of course, I took the last three floats of each of the 38 groups and threw them into matplotlib as if each of the triplets were a point in 3D space:

Boom. I had something that looked like a humanoid figure.

Do keep in mind that this took a whole day of staring at a bunch of bytes, but the feeling when I finally had the plotted coordinates was so, so worth it. Well, I supposed the next steps were to “connect the dots”, right? I then watched some hours of Blender tutorials on rigging, to finally try and understand what armatures really were, and what I should be looking for.

Ideally, most of the bones should be interconnected, so when you move a shoulder, the arm moves as well, and so do the fingers. If you twist the waist, their whole upper body should move accordingly. That strongly suggested some kind of hierarchy, which instantly made me think of trees. The only data on the file that could possibly have something to do with hierarchies and tree structures were the sequence of almost sorted 37 ints located right after the bone names and the points.

However, having one fewer than the number of bones kinda threw me off for a good while.

After more hours of staring at binary, I realized most of the bones were listed in an almost sorted order: L_Shoulder, L_UpperArm, L_ForeArm, L_Wrist, L_Hand, L_Finger1, L_Finger2, L_Finger3, L_Thumb1, L_Thumb2… All of that almost matched the number sequence in question, but putting both lists side by side didn’t make much sense, and neither did the names, until…

Until I realized there had to be a reference point for the whole model, a Base. The trick was that, although its name was listed first, it was actually the last point in the file. With that fix, I could now properly match the points and names. Moreover, the sequence having one less element than the amount of bones probably meant there was none for the Base bone, which made everything fit.

The number sequence was a serialized tree, with each integer representing the index of the parent bone, with 0 being the base (last bone). When I finally connected everyone to its parent…

I quickly wrote a Python script to load any .Skeleton and output their armature using what I had found so far. From experimenting with a bunch of other models, a couple of them seemed to be a little bit skewed, or with all of the points in the same plane, or with some other deformations, which probably indicates there’s data missing. Well, I guess it’s got something to do with all those other floats I completely ignored along the way.

Also, it was not that big of a surprise that all player characters had over a hundred bones each, complete with wing bones, skirt bones, weapon bones… Some of the main bosses also had more complex skeletons, and I then realized tackling the bank guy first was a great idea.

The .SkinnedAnims were still left untouched, for now. I did take a look at them, but I still feel that completing my understanding of the .Skeletons were a must before going further, so no advancements made there. Once more, I tried searching for answers and previous work online, when I stumbled upon…

6. Server Files and Game Source Code

I got my hands on a huge collection of files, along with tutorials on how to fire up a server, as well as the source code itself. I supposed all of that were leaked, somehow? This was mostly a general exploration, as an attempt to better understand the architecture and find the data tables and such.

Lunia’s servers ran on ASP, IIS, and MSSQL, all on top of Windows Server 2003. It’s interesting to note that it appears each Town Square was a single server instance, and each chat channel was also an independent IRC-based server. As the technologies used were ancient compared to the ones available today, and most of the files I had were barely functional, I have to admit I wasn’t much interested in trying to set up my own server or investigating further. After snooping around for some minutes, I turned my attention to the real interesting stuff: the game source code and development files.

Lunia itself was built on Visual C++, and seemed to have grown alongside its own custom engine, “XRated”. With it, there were dozens of custom tools to create and edit items, quests, pets, chests, and so on. A lot of code had the purpose of converting to and from those pesky custom file formats, and so they are probably very helpful for reverse engineering them.

All the “compiled” files found earlier in the client data could also be found here, like the .tga files that eventually generated all .dds 2D assets, all the .xml that eventually became the .b databases, and the uncompiled .fx shader code that were loaded in the client as compiled .fxc.

Here are the most interesting bits, and what I was actually looking for:

- A conversion table for items, skills and characters, to a unique integer hash, used in all other files.

- All item stats and properties (e.g. is tradable, is usable, cooldowns, level requirements).

- Tables for all fortifications and their stats multipliers.

- Tables for fishing rods, drop rates and other variables.

- All quest data, requirements and rewards.

- All shops, items for sale, sales prices, etc.

- Skills and its requirements, damage, cooldowns, etc.

I then grabbed most of the data tables and spent a day or two writing a dozen Python scripts to parse the .xmls and convert parts of them to JSON objects, which I plan to use later with the Pygame application from before.

The code documentation was… rough, to say the least. Lots of comments were in Korean, and the code style in general was definitely inconsistent - I did find a .txt that listed some guidelines, though! I also found a comment in one of the files that handled the animations, which simply wrote “banco de gaia - celestine”. I wonder if that was the song whoever wrote that piece of code was listening to at the time?

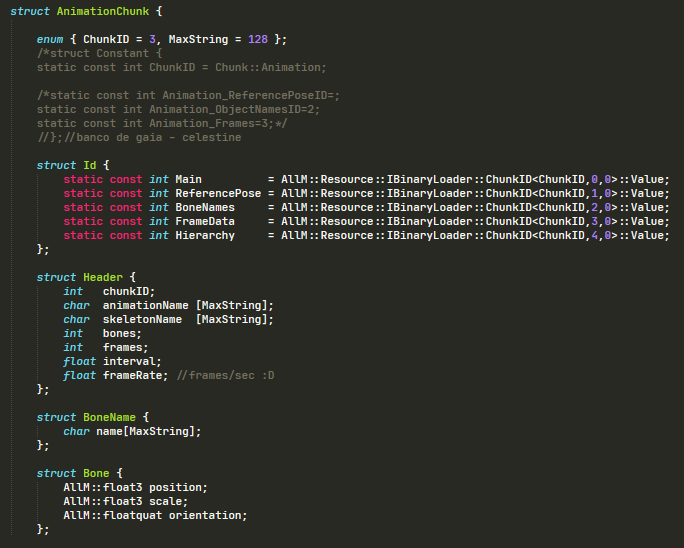

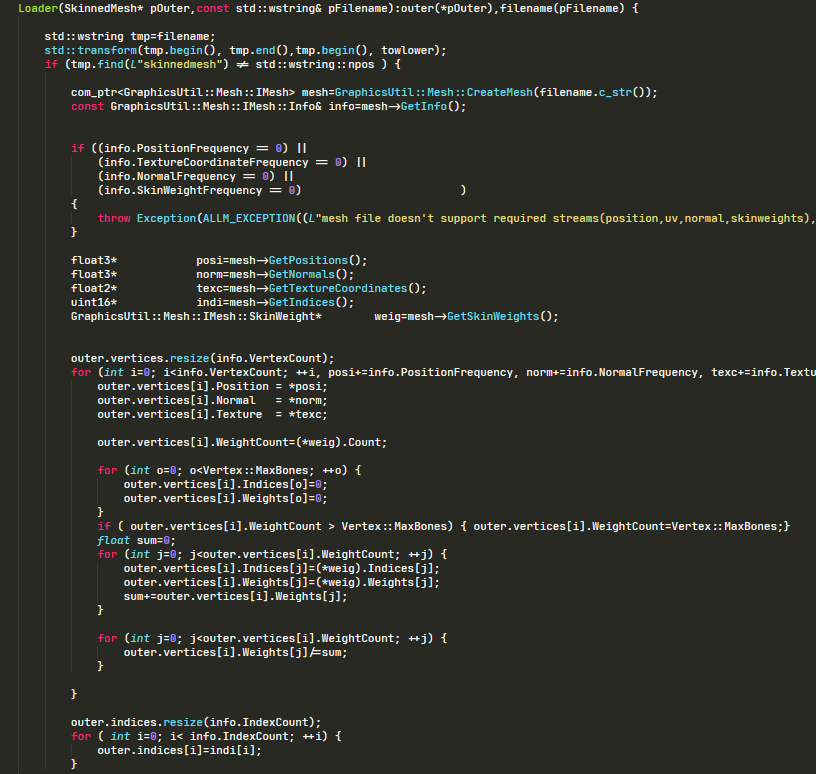

Of course, there was also all the code for the graphics rendering, like the one above. Most of them were also authored by juhnu, the same name found earlier. I managed to find the code responsible for loading the 3D model files mentioned in the last section, and some of my assumptions were confirmed, while others were corrected.

- The last section of the

.SkinnedMeshfiles are, per the code that handles it, “skin weights”. Not sure what to use them for, but oh well. .Skeletons are indeed composed of a header, a list of bone names, a bone hierarchy and a reference pose. A bonestructis composed of afloat3 position,float3 scaleandfloatquat orientation. Could the latter be a quaternion? Interesting….SkinnedAnims are made of starting and ending frames, a speed modifier, a list of frames, a list of bones, a frame interval and a frame rate. The animation code does give more hints on how to decompose the files.

There’s still a ton of stuff for me to go through, and I feel all of this was just a glimpse of the whole codebase. With that…

7. Future Work

As I wrote in the beginning, I still want to take all of this a lot further, which may make an update here or even as a whole new post.

Regarding the Python Inventory / Window Manager thingy, here’s what I’m planning as the next steps:

- Item shops, buying and selling, and the currency itself (in-game screenshot below).

- Item fortification, together with reagents and catalysts (in-game screenshot).

- Stats calculations based on class, level and equipped items (in-game screenshot).

- Fishing and all of its mechanics.

- Extract item data to an item server and API, so as to be able to have the whole item database accessible without having to load it all on every app startup, as well as to mimic more closely the original game.

- A “wardrobe” tool / model viewer, based on the currently equipped items. However, that wouldn’t be possible in Pygame, which is strictly a 2D library, so I would have to rewrite all of it in something else like Unity. That would be a whole new journey, once again starting from barely any experience, and I’m definitely looking forward to that.

- Overall tidying up of the code, and greater adherence to best OOP practices.

With regards to the 3D assets, I may continue to work on them by:

- Figuring out the remaining data in the

.SkinnedMesh,.Skeletonand.SkinnedAnimfiles and how to convert/export them to Blender. - Further exploration of Blender, 3D animation and modeling/rigging - maybe even rendering short animations based on Lunia’s models if my creativity and artsy skills allow.

- 3D printing characters to create small figures - if I manage to get access to a 3D printer.

At last, about the server files and source code:

- Finish opening and reading every single file and see what else I can find, as well as what logic I can replicate.

And… whatever else might pop in my head during all of that.

8. Closing Thoughts

It’s quite interesting to note how much software development has changed over the last 10 or 15 years. As I could notice by the server files and source code, there were barely any design patterns or previous work done on MMORPGs and game engines back then, as most of the filetypes, encodings and tools were homemade and custom to Lunia.

Furthermore, I don’t think I’ve previously worked on anything that mashed together so many different areas and technologies like this. Trying to reverse engineer as much as I can from Lunia has been a great learning experience, including regarding topics I never thought I would be interested in. It’s been a fantastic (and fun!) couple weeks, and I hope to have the spare time to keep exploring all of this for a while.

To wrap it up, shout out to @renatavinhaga, @DarkRyu550 and @gosiqueira for being extremely helpful in this whole endeavor. Finally, a big and heartfelt thank you to everyone involved in the making of Lunia. It definitely played a big role in my youth and in shaping me into who I am today, personality and career-wise. You are all my childhood superheroes.